Homer R. Kuck, German Prisoner of War Six Years Ago, Tells of Harrowing Experiences After His Plane Was Shot Down Over Hamburg—Sought to Evade Capture for Days

Homer R. Kuck

“Where were you six years ago today?”—we asked Lieutenant Homer Richard Kuck, of New Knoxville, pilot of a Flying Fortress during the war and today a member of the Air Force Reserves, sometime ago. His answer:--“I was a prisoner of war in Germany.” It was only after our third request that he finally agreed to an interview. We were so fascinated by Homer’s experiences that we want to share them with you.

Here is Lieutenant Kuck’s background. He is the son of Florenz and Hattie (nee Schneider) Kuck, south of New Knoxville. He was graduated from the New Knoxville High School in 1939, worked at the Hoge Lumber Company one year and then at the Monarch Machine Company in Sidney. He enlisted at Patterson Field, Dayton, on June 7, 1942. He took his basic training there as an enlisted man. He next volunteered for pilot training and was sent to Santa Ana, California, for pre-flight training. He was there until April, 1943. Then he was sent to Ryan Field, Arizona, near Tucson. On a certain day he made his first solo flight in the morning and was married in the afternoon to Annabelle Herron of Buckland. From there he was transferred to the Marana Air Base at Tucson for 9 weeks further training, and then to Marfa Army Air Base in Texas for multi-engine training. He was graduated as a pilot and commissioned as a second lieutenant. Then came a 10 day furlough at home. Thereafter his crew reported at Rapid City Army Air Base for training in the B-17, Heavy Bombardment. He remained there from November 1943 to March 1944. Upon completion of this training his crew of 10 was given a new B-17 complete with all equipment. They then flew it to Grand Island, Nebraska, and were given instruction for their flight overseas. Next they flew their Flying Fortress to an Air Base in Massachusetts where they were checked out of the country for overseas.

Fog engulfed the field. They made a take-off by instrument, flying by instrument all the way. They didn’t miss the airport at Goosebay, Labrador, by more than half a mile. They remained there two days and took off at night for Iceland. There they remained one day. From there they flew to Belfast Ireland, and then to the American Air Base near Cambridge, England. They were there from the latter part of April until their first bombing mission early in May. Their target was a German V-1 Rocket Site on the coast of France. Thereafter they flew about 4 missions a week, completing their 15th mission on June 15, 1944.

On Sunday, June 18, 1944, about 9 o’clock in the morning, their plane was shot down over Hamburg, Germany. Their elevation was about 25,000 feet. The two right engines were hit by anti-aircraft fire and both went dead. The plane was otherwise damaged also. It went out of control immediately and began spiraling and careening madly toward earth. Fortunately it did not go into a tail-spin. While it was in descent it was narrowly missed by the bombs that were dropped from other American planes higher up, one bomb missing them by not more than 10 feet. The crew worked frantically to get the Flying Fortress under control again and when they had reached an altitude of around 5,000 feet they succeeded. The plane leveled off and they headed in the direction of Sweden which was 90 or 100 miles distant. In Sweden they would be interned, provided they got there alive. But they were rapidly losing altitude, so rapidly in fact that after about 20 miles they were forced to crash-land in a large open field. “Did that experience scare you half to death?” we interrupted. “Yes, it did,” Mr. Kuck answered. “We were so badly shaken that we gave each other morphine shots which are ordinarily used for extreme pain only.”

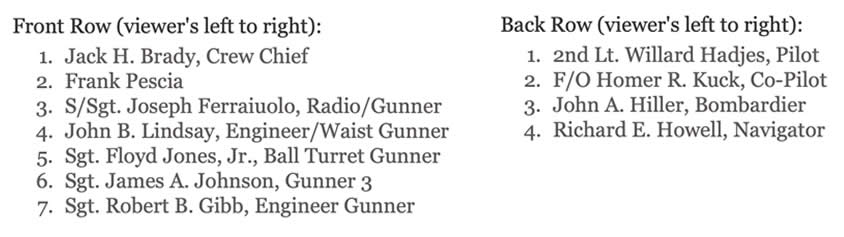

NOTE: This is the crew that Homer Kuck flew his missions with. The plane is the new B-17 named “Tailwind” which they flew to Europe. Number 5 in the front row is the man that Homer teamed up with for their escape attempt. This information is all available on the internet by doing a search on “Hadjes Crew”.

In the crash landing the crew escaped unhurt. The plane was already burning, we still had some bombs aboard, and we were in enemy territory. There was danger of an explosion. In accordance with instructions for such a contingency, we fired shots from our Very Pistols into the gasoline soaked plane and then it really started to burn. We separated at once, in pairs, and ran in different directions, running for our very lives. We were each equipped with automatics, but we threw them away, since it is healthier to be captured unarmed, than armed. Each pair was now on its own. Eight of the crew members were captured within an hour. My companion (our Turret Gunner, Floyd Jones of Missouri) and I, happened to go in a direction that wasn’t so closely searched, and so got away temporarily. We ran and crawled all that day until dusk to get as far away as possible. We rested about an hour and then continued walking, headed for Holland. We were in our Air Force uniforms, and were completely unarmed. We walked every night and rested during the day. The days were exceedingly long and the nights all too short.

Very early in the morning we would look for a hiding place for the day. This would usually be a barn or a hay stack, or any building or place that would give a cover. We spent one day in a farmers attic. Remember, the house and barn are usually connected there. We crawled into the hay-mow, and from there into the attic. The people were making hay, and they unloaded several loads of hay into the barn while we were in the attic of their house. They never guessed or suspected our presence. When night came and the hay unloading ceased, we crawled into the hay mow. After complete darkness we quietly got out of the barn and hit the road again.

“But after a few days we were getting terrible hungry and exhausted. We were almost completely without food. We each had an Air Force Escape Kit. We got water out of streams or open ditches, put it into our canteens and dropped a certain kind of capsule into the water. This made it fit for drinking. We were so hungry we dug seed potatoes out of farmers fields and tried to eat them. But try eating them, especially after they have been planted a while. At night we would sometimes milk cows, using the cup in our escape kit for a container. The German farmers milked their cows in the field, so we didn’t have much difficulty in milking them either. Being raised on a farm, I knew how. Our diet of warm cows milk and raw seed potatoes didn’t agree with us and we were both getting sickly and nauseated.”

“On the 8th day we couldn’t find a building to stay in, and so we hid in a thick forest. At daybreak we discovered that we were in a German military reservation. The area was used for target practice by the artillery. Shells began exploding overhead, branches from the trees started coming down, and then we saw German guards approaching. Now we thought the jig was up. However, as a last desperate measure, we crawled into an adjoining wheat field and lay down flat on the ground. Not suspecting anybody’s presence in the field, the guards passed by, were not more than 20 feet away from us, but they kept looking into the woods instead of the field. So we lay there all day and under cover of darkness safely got out. We found a barn to stay in the next day. We didn’t know it, but it was to be our last day of freedom. On the night of our 10th day after we were shot down, I guess we started out too early. We were walking down the road, headed for a little town the size of Lock Two. A man passed us on a bicycle, going in the opposite direction. A few minutes later he passed us again, headed for the village. He must have suspected and spread the alarm. As we were going through the little blacked-out town—we had to go through it, there was no way around—suddenly we were surrounded by about a dozen men. They questioned us and would not let us proceed. I tried to tell them, in the little Low German that I know that we were slave laborers, on our way to work at a certain town. Of course they didn’t believe us. So they kept us overnight in a tavern, four armed men guarding us all night. By now we were so sick and exhausted that we could hardly have gone further. We begged for food, but they didn’t give us any. The next morning the local sheriff took us to the nearest German Air Base, 20 miles distant. He rode a bicycle, but we had to walk.

PART TWO

Published July 25, 1950

Lieut. Kuck Questioned By German Intelligence Officer Who Had Complete Information Concerning Him—Former Prisoner Tells of Days in Prison Before Liberation

(The following concludes the story of experiences of Lieut. Homer R. Kuck, New Knoxville, after being captured by the Germans in World War II, following the bombing of his plane over Hamburg.)

Here at the Air Base they treated us swell. They gave us all that we wanted to eat, oatmeal, sausage, bread, etc. But our stomachs had shrunk to such an extent that we could eat very little. That night we got up four different times and ate as much as we could. But that never was much. The food tasted wonderful. The officers and men of the German Air Force treated us wonderfully, almost as if we were one of them.

The next day an armed guard took us by train to Frankfort-am-Main, to the German Air Force Interrogation Center. When we arrived my companion and I were separated and I was placed into a cell with an American Sergeant who had been taken prisoner in Berlin three days before. The next day I was placed in solitary confinement, into a cell 6 x 4 feet, with a cot, but no windows and no lights. It was pitch dark. The cell was infested with fleas, bed-bugs, and other vermin.

“On the following day I was taken out of this cell for interrogation by their intelligence officers. The man who questioned me was a tall Sergeant. He spoke perfect English. He said he was German-born, but had lived in California a number of years, having conducted a book store there. He offered me an American cigarette and I took it. He took a chatty, chummy attitude. When his questions began to deal with certain matters I told him that I was under oath to tell nothing except my name, rank and serial number. He wanted more, however. He didn’t threaten me in the least. Instead he smiled and quietly said—“Well, it doesn’t matter. You don’t have to tell me. We know all about you.” Thereupon the German Intelligence Officer opened a file and took out a sheet with my complete record. Then he told me: “Your name is Homer Richard Kuck. Your home is at New Knoxville, Ohio. Your father’s name is Florenz Kuck. Your mother’s maiden name is Hattie Schneider. You married Annabelle Herron. You worked at the Monarch Machine Company in Sidney, Ohio, before you enlisted—etc., etc., etc. He had information regarding me that my fellow crew members didn’t even have, and which could have been obtained ONLY from the files at the Air Force Base. He also told me when we left the States, the names of our crew members, when we landed in England, etc., etc. It was the most demoralizing information that I could ever have received. I neither said yes or no to the information he gave, but it was accurate and complete. Boy, what a let down! He could have gotten it only through spy work.”

“Not long after this a group of us were put into a French “40 and 8,”—60 men into a single car. We now travelled for a solid week, and the only thing we got was water. I was dirty, filthy, hungry, sickly and hadn’t shaved or bathed since we crash-landed. That trip was a nightmare. On July 7, 1944, we reached our destination, a German Prison Camp for captured allied airmen, “Stalag Luft 111.” Here were captured Air Force men from all the allied nations, prisoners of war of the Luftwaffe.”

“Did you meet your companions again?” “Yes, I did, but not till we reached Miami Florida after it was all over.”

“Life in prison camp soon took on a certain routine. There were many thousands of us in Luft Camp 111, at least 10,000. It was located at Sagan in Lower Silesia, 100 miles South East of Berlin. The only English newspaper permitted in the camp was the “O. K.” (Overseas Kid) a propaganda weekly from Berlin. It contained war news with a German slant, and such belated news from the States as Herr Goebbels office thought we should have. We also received the Deutsche Allegemeine Zeitung, and the Volkischer Beobachter. But these were especially valued because they came in so handy to stuff the cracks through which the icy winds howled when winter came.

This camp had 17 barracks, a shower building, theater, laundry and a fire pool. At 10 o’clock at night came the lock-up. The guards made their rounds, accompanied by huge German police dogs. All barracks had shallow tunnels running the length of the building. These were used by guards known as “ferrets” who used them to listen in on the conversation of the prisoners and to detect any tunneling operations on the part of the prisoners.

We slept in three-decker bunks. Each bunk was allowed 9 slats, no more, no less. The mattress was a burlap-like cover, filled with wood shavings. We were issued 2 light German blankets and one U. S. Army blanket each, but in winter we frequently slept with our clothes on to keep warm. We had a food locker in each barracks in which the food supply was kept. Red Cross parcels were issued at the rate of 1 per person, per week, at first. But as the number of prisoners increased this was reduced to half a parcel per person. These contained cigarettes, Army ration chocolates, oleomargarine, crackers, soluble coffee, cheese, sugar, corned beef, salmon, a cake of soap, jam, meat roll and prunes or raisins. The Germans issued black bread, potatoes, turnips, oleomargarine, jam, sugar, blood sausage and cheese occasionally, a few green vegetables in season and pea and barley soup. They issued each prisoner an eating bowl and cup, and a spoon, knife, and fork decorated with a swastika.

We also had a laundry. This was simply a small building equipped with two cement scrubbing tables with faucets and shallow basins running the length of the building. Hot water was not available. That made winter washing a shivering job. Soap was almost non-existent in Germany, and so of course none was issued to us. But we each got one cake in our Red Cross parcel, which meant a cake every two weeks.

We prisoners did everything imaginable to keep our minds occupied. We read, walked, went out and mixed with the others, talked, studied, staged dramatics, had singing sessions, played soft ball, had boxing matches, took turns at barracks duties, tried a little gardening, and just everything permissible that you can imagine. The guards were vigilant. Radios were not permitted but there was at least one carefully guarded set by which British Broadcasting Company news was received. The news received was guardedly circulated among the different barracks and the radio remained undetected. The German version of the news was broadcast through a public address system.

The prisoners were well guarded. Two large fences, each about 9 feet high and made of barbed wire, the fences running parallel, surrounded the entire camp. There was a barbed wire entanglement in between these fences. In addition there was a forbidden territory of about 30 feet from the fence itself, marked by a guard rail, surrounding the interior of the camp. You risked gun fire if you even entered this territory. The guard towers bordering the camp were manned 24 hours a day by guards armed with machine guns and powerful spotlights. Mail was slow in reaching us and letters were few and far between. Although my wife mailed three parcels to me during that time none ever reached me. She wrote me almost every day but I received only six of her letters during that entire time. The first that I heard from my wife was a cablegram through the Red Cross informing me that our son was born July 15. But the cablegram didn’t reach me until October.”

We next asked Mrs. Kuck concerning news from him on this end. She said “I was notified about 10 days after they were shot down that he was missing in action. I was expecting the baby just any time and the suspense was terrible. Not until some time in August did I get word that he was a prisoner of war, and well.”

On January 27, 1945, Mr. Kuck continued, the artillery fire of the advancing Russians could be distinctly heard and the German camp commander advised us to be ready to vacate camp in an hour’s time. The exodus began Sunday, Jan. 28, at 12:30 a. m. We marched single file. Each of was given an unopened Red Cross package. The weather bitter cold. We marched 62 miles in 6 days, arriving at the town of Spremburg. Here we were loaded onto French 40 and 8’s and went by Freight to Nurenburg, a miserable 2 day trip. The Camp at Nurenburg was a miserable wretched affair. It was vermin ridden, and in addition to the lice, fleas and bed bugs, there was a definite food shortage and there were frequent air raids. The march of 6 days plus 2 days in box cars had left us all in a physically weakened and mental irritable condition. We spent 2 full months at the Nurenburg camp.

By now the American seventh and Third Armies were penetrating Western Germany. On April 4, 1945, we again received evacuation orders. But now we had warm spring weather. This prevented much suffering. We marched 92 miles in 10 days. The Germans were taking no chance at having 10,000 trained airmen liberated. This camp was at Mossburg. We were there only 16 days. Soon after arrival things began to happen. American airplanes were very active. Cities were bombed all around us. Artillery fire could be heard distinctly. We packed our few belongings again, ready to march. Then the city of Mossburg itself was attacked by General Patton’s forces. Artillery fire took place only a few miles from us. On Sunday morning, April 20 things really began to happen. After the church service, held in the open in the recreation field, bullets began to whiz through the camp. Machine gun fire was heard. We all lay low to escape the rifle fire but a few of us prisoners were injured, none seriously. Mossburg surrendered around noon and our troops came straight for the prison camp. The German officers by now had fled. General Patton himself came to the camp and we yelled and shouted and cheered and cried. We’ll never, never forget the scene. Nor will we forget the feeling that came over us when the Swastika was pulled and when the STARS AND STRIPES WENT UP.”

“The liberation occurred April 29, 1945. We prisoners ransacked the German files in the prison camp and many of us brought our German “Prisoner of War Record” along with us.” He showed me his, complete with his photograph taken by the Germans and his finger prints. “In about 2 weeks time we were flown to France and I sent a telegram to my wife. We landed in Boston by boat on June 2 and on June 5 I arrived in Sidney and there my wife met me at the train. I had a 2 month furlough at home, followed by another month in Miami Beach, Florida. On November 5, 1945 I was mustered out of active service at “Camp Atterbury.”

Homer Kuck is today a First Lieutenant in the Air Force Reserves. He is Service Manager at Montgomery Wards in St. Marys and lives with his wife and son Stanley at New Knoxville.

Living Biographies

by Andrew Kay

In 1949 and 1950, Reverend Edwin Andrew Katterhenry (1900-1963), a minister and a native of New Knoxville, wrote the “Living Biographies” feature for the St. Marys Evening Leader under the pen name of Andrew Kay. These articles consisted of interviews with aging citizens, many from New Knoxville and St. Marys, relating their experiences from their younger days. After Rev. Katterhenry passed away in 1963, his widow, Florence Katterhenry returned to New Knoxville to live out the remainder of her years until 1982. For those of us who are grandparents today, we remember her as “Mrs. K”. In the final “Living Biographies” article Andrew Kay wrote about himself, thus revealing his identity to the general public.

NOTE: The “40 and 8” railcars mentioned were basically box cars which were intended to hold 40 men or 8 horses, so they were rather overcrowded with 60 men per car.