New Knoxville residents’ past crossed at home and abroad down through the years

By Sherri Diegel, Staff Writer (Published in the Evening Leader April 15, 1986)

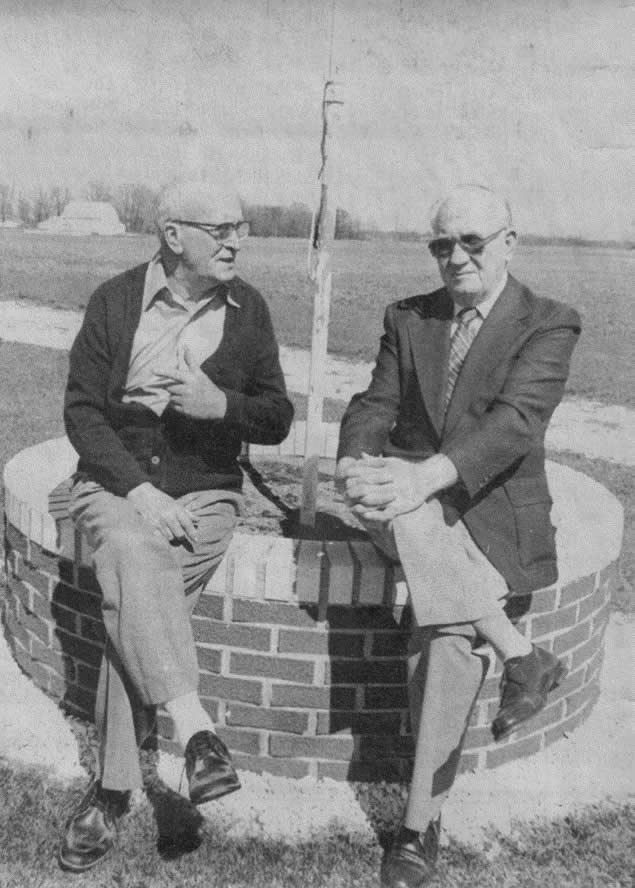

NEW KNOXVILLE—It seems Homer Kuck and Zelotes Eschmeyer have been shadowing each other all their lives. Wherever one ended up it seems the other was soon to follow—whether that place was a prisoner of war camp or a local restaurant.

They were born a few years apart in the town and entered World War II a few months apart. The Germans took them captive within a few months of each other.

On the same day in 1945 they were released from their respective prison camps. Now they share the same gathering spot each morning, a German-style restaurant, Adolph’s.

Eschmeyer, 68, and Kuck, 65, met recently at the former’s neatly kept white farm to talk over the days when they were underfed prisoners anxiously waiting for Allied forces to free them.

Looking back on the day 41 years ago when he was released from his barb-wire-enclosed prison, Kuck says, “I can’t believe what happened in the war. We lived through it.”

Kuck entered the fray first, by enlisting at Wright Patterson Air Force Base June 7, 1942. He volunteered for flight training, and on one day performed his first solo flight in the morning and married Annabelle Herron of Buckland in the afternoon.

His first bombing mission was in early May of 1944. At about 9 a. m. on June 18,1944 the Flying Fortress he shared with nine other men was shot down over Hamburg, Germany.

The badly shaken crew worked to bring the plane under control as it spiraled toward the ground, narrowly avoiding the bombs the other American airplanes were dropping.

After coasting for 20 miles, the bomber crash landed, and the unhurt crew members paired off. All but Kuck and his partner Floyd Jones of Missouri were captured within an hour. Unarmed and still wearing their Air Force uniforms, they ran and crawled during the night, then hid in barns or haystacks during the day. They slunk toward Holland for 10 days, weak from hunger, until they were nabbed by Germans. They were forced to walk to the nearest German Air Base, which was 20 miles away, while their captor rode a bicycle beside them.

Meanwhile, Eschmeyer was still in Ireland, awaiting his orders to head to the front. He had entered the infantry April 1, 1943, three days after he married Mary Minnich of St. Johns. He had arrived in Ireland in November of 1943. It was there “I got a letter saying Homer Kuck was a prisoner of War. I thought, ‘Gee, that must be a horrible life.’ A couple months later…” “You were one,” Kuck says. Eschmeyer’s capture didn’t occur until Sept. 21, 1944, two months after he joined the front lines in France. He was eight miles from the Moselle River, when his company was ordered to lay a road block. At 2:30 a. m. the Germans began raining shells on Eschmeyer’s outfit. Realizing they were surrounded, the Americans surrendered.

Though lice, bedbugs and bad food were common denominators for the New Knoxville men, other aspects of their imprisonment differed. Kuck spent most of his time in an immense barracks with 10,000 fellow Air Force officers. At Stalag Luft III in Sagan, between Berlin and Breslau, the living was relatively easy. “It was pretty nice. We had food and heat in the barracks,” he says.

At first, Red Cross parcels of chocolate, margarine, crackers, coffee, cheese, sugar, corned beef, salmon, soap, jam, meat roll and prunes or raisins kept him well fed. The Germans added black bread, potatoes, turnips, blood sausage, pea and barley soup and some fresh vegetables to the bounty. “One time we got meat (from the Germans) at Stalag Luft III. One week there was only one horse when there’d been two horses before on a two-horse wagon. I know it (the meat) was that horse.”

But as the number of prisoners mounted, the food supply dwindled. As it did so, the men began concocting traps made of twigs to snare birds. Six birds would make a soup, Kuck relates. Though letters from home rarely made it to the prisoners a chocolate cake, dried out but intact, made it from his wife’s to Kuck’s hands one time.

But the news that he most anxiously awaited, the news that his child had been born, took months to arrive. Stanley was born in July, one month after his father’s capture. The telegram announcing his birth arrived in October.

Lieut. Kuck and his comrades whiled away their days not doing hard labor, since they were officers, but attending college classes taught by men who had been professors or other types of professionals before the war. “We could go to school and take almost any subject you could think of,” Kuck recalls. When not in class, the prisoners spent some of their time trading soap, cigarettes, and chocolate for more substantial food or anything else they wanted. “I bought a horse and cart for 100 cigarettes. I think I could have bought a house for 6 bars of soap. If I could have gotten 10 cartons of cigarettes I could have bought a castle. I’d be the Duke of something or other.”

The POWs also passed the time plotting escapes. “It was your duty to escape if you could, and your job to help others escape,” Kuck explains. “Those who escaped were picked. They were smaller, wiry, in good condition. I was too big. My job was to get rid of the dirt (from escape tunnels the prisoners dug).” Kuck managed to do so by sewing one pair of pants inside another. He would drop dirt down the space between the two pants. After the space was full he would walk around the compound, pulling a string which released the dirt from the hem area. “The ground raised six inches during the six months I was there, but the Germans never noticed it.”

Neither did the Nazis notice the escape hatch inside Kuck’s barracks. The men had dug a tunnel under the heating stove. When the guards or “goons” weren’t watching, they would pull the stove out, remove the bricks and dig. “The goons were always looking for tunnels, but they wouldn’t find ‘em. We had tunnels in our camp started by the British captured after the fall of Dunkirk in 1939. Some of the prisoners had been there that long and had it tunneled. Did you ever watch Hogan’s Heroes? It was exactly like that.”

“Aw, Hogans Heroes…” Eschmeyer interjects. “It wasn’t like that. We never had women come in.” “We never had women either,” Kuck says. “It was the tunnels I was talking about.” At any rate, the escapes were so well planned that the chosen few were supplied with maps of the area which would guide them once they were outside the compound. But the penalty of capture was rather stiff. “They shot 90 shortly after I got there,” Kuck says. “What was the advantage to escaping?” asks Eschmeyer. “To get back to the outfit and get the war over with,” Kuck replies. “The last three months there were no escapes because we knew the war was over.”

During those last months the easy living came to an end. Jan. 28, 1945, the 10,000 POWs willingly were evacuated from Stalag Luft III by the Germans as they heard the Russians approaching. “We didn’t know what would happen if the Russians liberated us. We’d rather move and be liberated by the Americans or Canadians,” Kuck claims. Fear of the Russians was shared by the Allies and Axis forces alike. “I saw carloads of frozen women and children. They’d get on flatbed cars in subzero weather and go west. They’d do anything to get away from the Russians.”

Though the POWs fared better, their six-day march through freezing weather was not pleasant. “I had no boots, no gloves. I had a British overcoat I’d cut off and an army blanket.” The 62-mile trek ended at Spremburg, where the men were crammed into breezy cattle cars. The two-day train trip ended at Nuremberg’s Stalag XIII-D, where there was virtually no food. During his two-month stay in Nuremberg the normally 5-feet-11-inch-tall, 190-pound Kuck dropped to 120 pounds.

April 4, 1945 the POWs were again ordered to march. The 92-mile trudge in 10 days was much more pleasant than the January one because of the warm weather. Kuck spent only 16 days at the new camp in Moosburg, anticipating liberation. April 29, 1945 Gen. George Patton and his troops fulfilled his wishes. Kuck and his buddies cheered and cried as the swastika-bearing flag was pulled down and Old Glory was hoisted up.

Before he was flown from Germany to Rheims, France, Kuck and the other POWs got a long-needed grooming session. “We walked to a delousing station, got a shave, deloused and a haircut and all new clothes.”

At Camp Lucky Strike in LeHavre he met up with Zelotes Eschmeyer, who had been liberated the same day. They returned to America on separate Liberty ships. Though they can’t recall their conversation when they were united at camp, it probably included a comparison of their prison treatment.

Whereas Kuck spent much of his time gaining knowledge, Eschmeyer, who was not an officer, spent most of his imprisonment working from 7 a. m. to 5 p. m. weekdays and until noon on Saturday as an assistant to a carpenter in Wilheim, Germany. He had 23 companions as opposed to Kuck’s 10,000.

Eschmeyer proved an all-round handyman, doing tasks from building baby cribs to making broom handles to chopping firewood for the 7,000 people of the town. His steady diet was barley soup and black bread, plus the occasional bottle of soda pop or beer he bought with his salary of six marks a week. Life in Wilheim, where he stayed from Jan. 22 to April 29, 1945, was more pleasant than his first three months of captivity.

For the first two days after his Sept. 21, 1944 capture he was kept in a brick building with 200 men and thousands of fleas and bedbugs. Then he spent three days and nights in a boxcar with 50 fellow POWs, a little food and no water. At his first camp Stalag XIIA in Limburg he received a Red Cross parcel. After three weeks in that camp, Eschmeyer and 499 other Americans took another “miserable train ride” to Stalag VIIA in Moosburg.

With about 1,500 workers, he was sent to Munich daily to “clean up what our bombers destroyed.” It was from Moosburg that he was sent to work in Wilheim. During his incarceration there he kept a diary. His entry for April 19 reads: “Wilheim was bombed at 10:30 a. m. Rail way station (Banhof) blown to bits. Did I sweat!”

He remembers well April 28 in Wilheim. “The night before we were liberated they (Germans) came and got me. They gave me 10,000 Domino cigarettes. They (fellow POWs) set there smoking all night. We couldn’t see each other (for the smoke).” When the liberators stormed into town he recalls “every window had bedsheets hanging out of the window.”

On that momentous day he wrote: “Recaptured by 116 Cavalry at 10 a. m. Leading element of 12th armored division. A great day! Now we can get some good chow and plenty to smoke again. Am ready to go home and stay there after two years away from home and 18 months of that overseas. Where is my “Discharge” from the armed services?” His discharge finally came Oct. 26, 1945, four months after he’d returned to the United States.

During the 41 years since their release Kuck and Eschmeyer have lived, raised children and worked in their hometown. After spending 20 years in the television and appliance business, Kuck is now a self-employed refrigerator repairman, and Eschmeyer is retired from 40 years of employment at Hoge Lumber Co. Though they keep their afternoons full, the ex-POWs can be counted on to sip a cup of coffee with their friends at Adolph’s each morning.