INTRODUCTION

In 1962 Edwin Richard (E. R.) Kuck, founder of Brookside Laboratories, wrote an extensive treatise entitled “An Historical Account of the Early Religious and Social Life of the New Knoxville, Ohio Community from 1836 to 1900”. As part of this treatise he wrote a detailed three-part biography of his great-grandfather, the Reverend Frederick Herman Wilhelm (F. H. W.) Kuckherman, who came to our community as a young immigrant from Germany. Although this first installment of the biography is entitled “Henry Kuck, 1821-1852 – as Immigrant, School Teacher, Physician and Religious Leader”, it actually tells the story of the Reverend’s life from his immigration from Germany until his full retirement to his farm in 1894. Photographs of the Emmanuels Church and the Reformed Church have been added to this part of the biography.

HENRY KUCK, 1821-1852 – as IMMIGRANT, SCHOOL TEACHER, PHYSICIAN and RELIGOUS LEADER

Rev. F.H.W. Kuckherman

1821-1915

The Reverend Kuckherman was born October 17, 1821, on a rented farm near Ladbergen, Germany. He was the third son of Gerhard Heinrich Kuckherman and his wife Katherina Elizabeth, nee Kuck. On October 28, 1821, he was baptized Frederick Herman Wilhelm Kuckherman.

Being one of six children, his opportunities for schooling were limited. Because of his desire for education, he disciplined himself at an early age to use every opportunity to improve himself through self-training and home study.

At the age of 19 years, he decided to follow his older brother, William H., who had migrated to the Knoxville, Ohio, community several years before. He felt that here would be ample opportunity to accomplish and fulfill his educational desires. Several years later he was to be followed by his remaining brother and his three sisters.

Upon his arrival in Cincinnati, he changed his name to Heinrich (Henry) Kuck. The reason for this was that he was still eligible for military service in Germany, which he detested. The fact that he had migrated to America did not release him from military service and he could be returned to Germany if apprehended.

After thus disguising his identity, young Kuck took advantage of any and every opportunity to learn the English language. Through the medium of the Cincinnati church, he became acquainted with a teacher who agreed to tutor him. This was to continue throughout the ten months he spent in Cincinnati while working off his travel bond obligations.

After his ten months stay in Cincinnati, he had not only worked off his travel obligations but had saved enough money for a possible investment in the Knoxville community. Besides, he had acquired a basic training in the English language, which he would further develop from a set of English textbooks he had acquired. When he was ready to move to the Knoxville community, he had no interest in purchasing the special “Pioneer’s Kit” with which all pioneers equipped themselves. Instead he purchased books, which included a German-English Dictionary, a German-English Bible, and – of all things – a book entitled “The Pharmacopea of Homeopathic Medicine”.

Upon arriving in Knoxville in November of 1841, he found conditions not as exciting as his older brother’s letters had promised. The community was still a hopeless wilderness, and there was much to be done. After settling in his brother’s home, he found temporary work on the Cincinnati-Erie Canal, where he earned wages of fifty cents per day. However, manual labor was not to his liking. The community would soon need a school and a teacher, so he studied hard to procure a license for teaching. Consequently, during the summer of 1842 he walked to Lima, Ohio to take the special examination which, upon passing, would give him the necessary license to teach.

An amusing incident of this examination concerned one of the questions on the subject of arithmetic. The question was, “How many zero’s are there in one million”? To this he answered “six”; again he was asked the same question, to which he again answered “six”. Then his examiner asked him to write the figure 1,000,000 on paper. After writing out the figure, the examiner was quick to see his own mistake and, needless to say, young Kuck had earned his license.

While the church records of these early years reflect the religious experiences of the community, they fall short in revealing the general social advancements of the time. However, the school attendance book and the account book kept by young Kuck during this period shed much light on the events of those days. Both of these highly prized books are in the possession of the author.

In this attendance book, which was kept by Henry Kuck as teacher, we find the following noteworthy school facts covering the period of 1842 through March 1853:

- The school was conducted in the Reformed Church built in 1840.

- Attendance was on a subscription basis. The tuition paid by the parents was 5 cents per pupil per day, making a full month’s attendance $1.00 per pupil.

- The school year was divided into two semesters of three months each. During the first term, covering October, November and December, only German was taught. The term starting in January and lasting through March was devoted entirely to the study of English.

- The school day started at 8:00 A.M. and ended at 12:00 Noon.

- The first year’s attendance, starting in 1842, records the names of 13 pupils – all boys. The attendance for 1852 records the names of 27 pupils – all boys.

Of further interest are the signatures used on the fly page for each school term. For the years 1842, 1843, 1844, 1845 and 1846, we find the double signature – Heinrich Kuck, Schulen Meister and Henry Kuck, Teacher

The fly pages for the years 1847, 1848, 1849, 1850 and 1851 carry the single signature: Rev. F. H. W. Kuck, Teacher. On the fly page for his last term as teacher – 1852 through March 1853, his signature appears as Rev. F. H. W. Kuckherman, Teacher.

By carefully tracing the names of his pupils to their family affiliations, we discover that he was teaching the youth of as many Methodist families as of the Reformed families regardless of the fact that he was – in the later years – the nominal head of the Reformed Church.

With Kuckherman’s ordination as minister in 1852, he could foresee strife and confusion concerning schooling in the community. While his own congregation gave him forbearance in including the youth of Methodist families in his school conducted in the Reformed Church, he doubted if a new schoolmaster could avoid the contention – from both churches – that might arise.

After carefully evaluating his future obligations as the permanent pastor of the Reformed Church and realizing the special attention he must give to the construction of his new church in 1853, he saw no way in which he might continue as the community’s school teacher. Therefore, to avoid new contentions and frictions he called a joint meeting of the families of both the Reformed and Methodist Churches in September 1852, and exhorted them to build a community school through their joint efforts. Because of the great reverence that the members of both churches had for this natural leader and which had blossomed forth in their community, his suggestion was unanimously approved and carried out.

Through this action, the now Reverend Kuckherman displayed his talent as a great leader and coordinator. A frame school building was accordingly built and made ready for the first class to begin October 1, 1853, and a new teacher – H. W. Snethkamp, a nephew and former pupil of Rev. Kuckherman – became the first teacher. Not only had the community received its first public school, but by his wise guidance he had led the people of both churches to cooperate, side by side, in a common enterprise. This healing influence within this community of families was a most remarkable contribution.

Having thus completed the record of young Kuck’s career as a school teacher, let us return to the year 1842 and examine other phases of his many-sided life. Of equal importance to his career as school teacher was his role as the community’s physician. There was no physician in the young community and people did become sick.

Through self-study and training, he had pretty well mastered the contents of the Pharmacopea of Homeopathic Medicine which he had purchased in Cincinnati. While he never attempted surgery or bone-setting, he did prescribe and provide his home-made medicines for other ailments. For more than twenty years, he was to be their only doctor and his competence was highly regarded and respected by all.

However, in 1862 Rev. William Eckermeyer became the minister of the Methodist Church. Mr. Eckermeyer had previously graduated from the Cincinnati Medical College before he took up the ministry, and while in Knoxville fulfilled the dual calling of minister and doctor. Besides being teacher, physician and minister, Rev. Kuckherman was also to become the confidential advisor of many families. Many and varied were the problems submitted to him, and each problem was confidentially and graciously treated. The people had learned to depend upon him.

For the young teacher Kuck, the year 1843 forecast another important event in his life – he had fallen in love. On January 31, 1843, Adolph Meckstroth, age 23, and Henry Snethkamp, age 28, who had married sisters nee Quiller and were living together in one home on the well-known Charles A. Meckstroth farm, were both simultaneously killed while felling a tree. Having been asked to conduct the double funeral services, Rev. Kuckherman himself was stricken with grief at this unfortunate accident. In his efforts to console the grief-stricken widows, he suddenly found himself in love with the widow Meckstroth.

Upon acceptance of the Reformed Church’s offer of free use of the parsonage in exchange for leading the congregational services, he saw fit to propose marriage. Consequently, on March 18, 1844 he married the widow Mrs. Maria E. Meckstroth, nee Quiller. This union was blessed with a son Ernst William and a daughter Christine Elizabeth (Mrs. Herman Knierim). Unfortunately this marriage was to be of short duration because of the wife’s untimely death.

He later married Miss Maria Lageman, a member of the Cincinnati church, with his friend and champion – the Rev. Braasch – officiating. To this union was born a son, William Jr., and this wife was to live to the ripe old age of 89 years, her death occurring on September 29, 1911. Of special interest concerning his two marriages is that in the first ceremony he was married as Henry Kuck and as Rev. F. H. W. Kuckherman in the second.

Soon after his marriage in 1844, young Kuck was to add yet another interest to his wide range of activities. His growing popularity in the community caused more and more of his members to seek his advice, much of which concerned their farming problems. Having had no previous inclinations toward farming, but realizing that he could not escape its importance with his members, he decided to inform himself on this subject. So he decided to purchase a farm.

His search for a farm was made with deliberate thought and studious planning. He wanted a farm with a running stream that would run through the length of the farm. So he began to scout the entire area, until he found exactly what he wanted. Of further interest to him was the discovery of a small clearing on this land on which were growing fourteen half-grown apple trees, probably planted by the famous Johnny Appleseed. Furthermore, it was located only one-half mile from the village.

Having thus found what he desired he lost no time in registering his application for this parcel of land—comprising 80 acres. Sometime after October 1, 1846 he received the Land Grant Certificate No. 12,921 for this parcel, and a copy of this land grant is included in a foreword section of this treatise. It is of interest to note

that this certificate is registered in the name of Henry Kuck. Because of his triple activities as schoolmaster, preacher and doctor at that time (1846), he had little time to devote to his new acquisition to which he proudly referred as his “Lauter Bach Ackern” – (Brookside Acres). Although he did not attempt to clear any part of his land until the early sixties, he began almost immediately to inform himself on the latest scientific information concerning the business of farming.

By the early sixties, the now Rev. Kuckherman had been relieved of his responsibilities as schoolmaster, and his duties as the community’s physician were now shared by Reverend Eckermeyer of the Methodist Church. Furthermore, his pastoral duties in his church had assumed routine form. He was never known to have prepared a written sermon. His oratorical ability permitted him to talk extemporaneously – always direct from the heart.

By the year 1860, his son Ernst had reached the age of 15 years, which also meant that he had reached work age. He needed to be taught how to farm in the most scientific manner, and Rev. Kuckherman would be the teacher. Through Ernst he would prove all the most modern practices of farming that his extensive reading had impressed upon him. So they started out together to clear the land, but in this effort they were to be quickly assisted by friends and neighbors who insisted on helping them in lieu of the various and sundry favors Rev. Kuckherman had extended to them over the years.

By thus coming intimately in contact with the conditions of his own land, he was to quickly realize that the major problem on his farm, as well as on the other farms of the community, was the wet and swampy conditions that plagued a large part of the land. The land needed to be drained. But how could this be accomplished? This problem was to become his principal concern – not only for his own farm but for the others a good solution of this problem would be a boon.

Consequently, Rev. Kuckherman began his research on this problem with all the energy and craft he possessed. Because of his incessant reading, he found that a company in Pennsylvania had patented a machine for the molding of wet clay into cylindrical tubes with a reinforced flat bottom and which, when fired in a hot kiln, would produce a ceramic hollow tile that could be used for sub-surface irrigation. This was in 1862 and it immediately fired Rev. Kuckherman’s interest and imagination. He corresponded with the company for complete information about its operation, the cost of the machinery, its installation and, particularly, as to how to build and operate the kiln.

Of further interest to him was the introduction of a special bill in the National Congress, called the Public Money Drainage Acts, which would provide for the advancement of funds to land owners to enable them to make improvement of their lands not only by drainage, but by irrigation, the making of permanent roads, clearing, erecting buildings, etc. This bill was passed in 1866 under the title of Land Improvement Act. Under this act farmers could borrow money from the government to cover their costs of irrigation and have it charged against their property values. The repayment of such loans was by equal installments payable semi-annually with 3% interest, extending over a period of ten years.

Here then was the answer and he proceeded immediately to acquire the necessary equipment and machinery to build the buildings and the kiln for making tile – for how else could the people in the community benefit from this act if they did not have the tile available to them? The G. H. Kattman version of this early venture, crediting the building and operation of this first tile mill to Herman H. Meckstroth, is in error. All of the records concerning invoices for machinery and the building of the mill structure and kiln, which records are still at hand, are in the name of E. W. Kuck and Company. This E. W. Kuck was Ernst, the son of Rev. Kuckherman whose personal identity is carefully disguised under the term “Company”.

However, during the year 1870 a partnership was established with Herman H. Meckstroth. Under the date of December 9,1870, we find the first evidence of this partnership from an invoice ordering a replacement of a “mud wing” for the machinery. This invoice for $2.08 is made out in the name “Kuck and Meckstroth” and further carries the guarantee: “We will build this mud wing thicker, so that it will crush any stone you may get in it or stop the horses”.

Building the Tile Mill

The building of this tile mill was started late in 1866 and finished in late 1868 on Rev. Kuckherman’s land. It was built over the carefully engineered plans prepared by Rev. Kuckherman himself, who also supervised every phase of its construction, particularly the building and construction of the kiln. The tile making part of the mill itself commanded a building 40 feet by 60 feet. To the north side of this building was another roofed but unsided shed that accommodated the treadmill for a team of horses that provided the “horsepower” for this operation.

On the south side of this structure was the curing and storage shed, which was 120 feet in length and 48 feet in width. Including the tread mill shed and the brick constructed kiln 30 feet to the south of the curing shed, the overall size of the total structures would average more than 200 feet by 48 feet in dimension. It may be safely conjectured that in its day it was the largest manufacturing establishment in all of Auglaize County and, furthermore, it is almost certain that this tile mill was the very first tile mill built in Ohio and the entire Northwest Territory. Because of the Land Improvement Act, tile companies sprang into existence all over Ohio in vey short order, but it is doubted that any got into operation before the one in New Knoxville.

A careful review of this enterprise indicates that from 1866 to 1870 this enterprise was operated under the name of E. W. Kuck and Company. All the financing for this enterprise was supplied by Rev. Kuckherman himself, and by loans made to E. W. Kuck upon Rev. Kuckherman’s personal guarantee. Because the demand for the tile was from the first greater than their ability to supply them, the enterprise was immediately successful and all obligations were fully paid off by 1870. In 1870 Herman H. Meckstroth purchased Reverend Kuckherman’s interest in the enterprise and assumed the managerial duties of the new partnership under the name Kuck and Meckstroth.

By the year 1875 another change was to be made in this enterprise. At this point William Kuck, Jr., the youngest son Rev. Kuckherman, had grown to manhood and was ready to assume his responsibilities. By this time the oldest son, Ernst, had tired of the eternal job of firing the kiln and had personal aspirations to own his own farm. Through family consultation, therefore, it was contrived that Ernst would sell his interest in the tile making business and purchase a farm which was being offered for sale in Shelby County, Ohio. Consequently, on February 28, 1875 E. W. Kuck purchased from the estate of John Bates the farm comprising 100 acres for a consideration of $2,150.00. This is the same farm now owned and operated by Lewis Kipp.

Thus in 1875 Herman H. Meckstroth became the sole owner of the tile making enterprise. E. W. Kuck moved to his own farm in Shelby County and William Jr., Youngest son of Rev. Kuckherman, became the tenant of Kuckherman’s own farm and continued to tenant the farm until 1890 when Rev. Kuckherman himself would move on the farm, after resigning his pastorate.

The foregoing treatise has been given in intricate detail in order to properly portray the tremendous mental and organizational ability of Rev. Kuckherman and to observe other facets of his very active and many-sided life. Of first consideration was his extreme modesty. In this, as in all other activities throughout his long life, he carefully disguised his identity in the enterprise, although he had directed it from start to finish. Of second importance was his concern with the immediate problems that affected the welfare of his members concerning their farming problems, how he adapted himself to their problems and how he made an effort to help them. While his efforts in solving the irrigation problem of their lands was possibly his most important contribution, he provided many more innovations for the benefit of his members.

Following his religious concept that man cannot live by bread alone, he also felt that the body cannot exist without the bread. So he adopted the idea of a dual ministry – his ministry to God and his ministry to agriculture. His members needed both services. So while he performed his pastoral duties through the church, he became more and more the community’s specialist in agricultural affairs, for which he masterfully qualified himself by virtue of his avid and extensive reading.

In the role as the community’s agricultural specialist, he introduced the idea of crop rotation. On his own farm he introduced and experimented with many new varieties of wheat, barley, oats, corn, potatoes, etc. In 1876 he introduced the first Dodge. No, not the automobile but the Dodge Reaper, just then coming on the market. In turn he introduced the sulky plow, the mower, the corn planter and the McCormick binder.

While the Reverend had thus advanced his interests and knowledge on matters relating to the business of farming, he did not neglect his interests in church matters. In fact, after selling his interest in the tile making enterprise, he began to give serious attention to affiliating his congregation with some denominational order. For thirty years he had conducted the affairs of his church as he had wished. No one had questioned him, for he represented to them exactly what they wanted in a leader and pastor.

While this had been a most desirable relationship for him, he realized that some time he would have a successor, and then what would happen to the congregation? With his characteristic tact, he suggested to his congregation that it affiliate itself with the Reformed Church of America. Because he and practically all of the members had been members of the Reformed Church in Germany, his suggestion was enthusiastically received and approved.

Accordingly, the congregation was received into the fellowship of the Reformed Church in the United States by the Heidelberg Classis in 1874, then under the jurisdiction of the Synod of the Northwest. To complete these affiliation ceremonies, Mr. Heinrich Lutterbeck was chosen to attend the classis session as delegate elder. The pastor himself did not go to the meeting, nor did he ever attend a classis meeting, but always sent a delegate elder. It was the elders, each year a different one, and not himself that should become trained in the affairs of the denomination when his pastoral duties in the congregation would come to an end.

By the end of the year 1875, Rev. Kuckherman had realized a satisfactory solution to practically all of his carefully and shrewdly engineered plans. His oldest son had disposed of his interest in the tile making enterprise and was now living on his own farm, and he had found a denominational home for his congregation. From this time forward his labors were to follow a routine course for fifteen years.

During the year 1889, Rev. Kuckherman became afflicted with a painful and what was to him an embarrassing gall bladder condition. This condition caused him to consider resigning his pastoral duties and to make many plans. First he would have to leave the lovely new parsonage that had been built in 1888. Naturally he wanted to move to his farm which was then tenanted by his youngest son, William Jr. To facilitate this matter, he helped his son purchase a farm in the northeastern section of Washington Township, of which William Jr. took possession early in 1890, thus leaving his own farm available to him.

Then, with all the arrangements completed, he tendered his resignation before the congregational meeting held on May 26, 1890. The copy of his resignation has been carefully preserved in the congregational records and reads as follows:

“Dear Brethren:

My years are drawing to a close; they are approaching seventy and my strength is ebbing. My physical infirmities increase, my memory often fails me, and frequently I enter the pulpit in pain. I therefore feel compelled to announce my retirement. The Consistory in cooperation with the congregation will kindly seek a successor during the coming months. Should a successor not be found by September I shall, if it be the desire of the congregation and if God give me strength, continue until a suitable minister is found. Beloved, I thank you most heartily for the love shown me during the many years we have lived together in joy and in sorrow. My love will ever go out to all of you, and I shall remain a faithful member of the congregation. I commend myself to your prayers until we shall gather there where we, in the fullest sense shall find rest from our labors and be freed from every trouble.”

To this request the congregation responded by giving expression to the gratitude that every heart felt was due the aging pastor who, in labor and toil, in love and faithfulness, for them had spent his life. It was further resolved that after his retirement the pulpit should remain open to him; also that the congregation and his successor would welcome his help and cooperation as circumstances might require.

In consequence of this action, Rev. Abraham Schneck of Louisville, Kentucky preached a trial sermon on Sunday, July 2, 1890 and was unanimously elected by the congregation. On September 1st, Rev. Schneck moved into the parsonage, and with that the pastoral duties of Rev. Kuckherman had come to a close.

Thus had come to an end nearly 50 years of unselfish pastoral and community service. In the pulpit or in public, Rev. Kuckherman’s character was ever unassuming and genuine. He shunned the limelight. It was inherent in his nature to do so. He participated in classical and synodical gatherings to a minimum. He felt himself called to do two things – to preach and to teach the Word of God, and to serve his fellow man in any capacity that his many and varied talents permitted.

At this point, we may summarize his pastoral achievements. At the time of his retirement in 1890, the membership in his church, including children, exceed the 800 mark. At the same time the membership of the Methodist Church had dwindled to less than a dozen family names, representing less than 80 souls, including children. It is noteworthy that throughout his pastorate Rev. Kuckherman maintained the finest and friendliest relations with the families of the Methodist Church. His wise counsel was as freely given to the Methodists as to members of his own congregation. His account book shows many personal contributions made to the Methodist Church during its struggle for survival. Such generosity was but a natural consequence of his magnanimous character, for had not many of these members been his pupils during his schoolmaster days, and was not his own sister Sophia Elizabeth who had married James Slack, a lifelong member of the Methodist Church?

By late summer of 1890, Rev. Kuckherman had retired to his beloved “Lauterback Ackern” (Brookside Acres), a name later changed to Brookside Farms, to continue for another twenty-five years. To conduct the actual farming, he depended upon his grandson – Henry Kuck – whom he had adopted and raised in his own home since the age of four days, when his mother, the wife of Ernst Kuck, had died after his birth. Having thus retired from the ministry and having established residence on his farm, he decided to re-assume his self-selected name – Henry Kuck – the name he had used when he first came to the community; the name in which he had been married; the name that appeared on the deed for his farm, as well as the name he used during his teaching career.

His full title and name of Rev. F. H. W. Kuckherman was entirely too long and had been forced upon him as a condition of his ordination as a minister. So now that he was no longer engaged in the ministry, he felt guilty in continuing the pastoral name and, for this reason, he proceeded to again use the name Henry Kuck in all of his business transactions.

But there was a complication – his grandson’s name was also Henry Kuck. For this he had a quick answer. He would simply have his grandson adopt the letter “O” as a middle initial in his name, namely, Henry O. Kuck. This action created an amusing situation, for his grandson had been affectionately labeled up to this time as “Pastor’s Heiney” (Pastor’s Henry). The novelty of this change in name created an immediate impression in the community, so that from that moment on he was nicknamed “H. O.”, which appellation he was to carry until the day of his death.

And so he had settled down to a quiet and peaceful rural life that was to be soon and suddenly jolted by a growing discontent in the church he had established. It seems that the new minister – Reverend Schneck, during a congregational meeting, exhorted them to modernize the services, particularly by replacing the old Psalter (songbook without musical notes) by a modern Hymnal. When the congregation voted against this demand, Rev. Schneck undertook to scold them for being so backward and out of date.

Actually, Rev. Schneck – at the time of his appointment to the New Knoxville church – was regarded as one of the most prominent and progressive preachers in the entire Reformed denomination. Very personable by nature, he was also ambitious and aggressive in everything he attempted. His greatest weakness stemmed from his short-fuse temperament. During Rev. Kuckherman’s pastorate, the congregation had been led by suggestion. Rev. Schneck tried to drive them, and to this they were unaccustomed, so his position was quickly resented.

So violent was the reaction to Rev. Schneck’s dictatorial demands that within eight months from the start of his pastorate his position in the congregation had become unbearable and highly untenable. Strife and confusion reigned unchecked. As a consequence, Rev. Schneck was approached by a committee favorable to him to organize a new congregation, which challenge the aggressive Rev. Schneck willingly accepted.

As a consequence of this decision, more than a third of the old congregation joined the movement to follow Rev. Schneck in the formation of a new congregation to be named “Emanuels Church”.

The Emmanuel Church

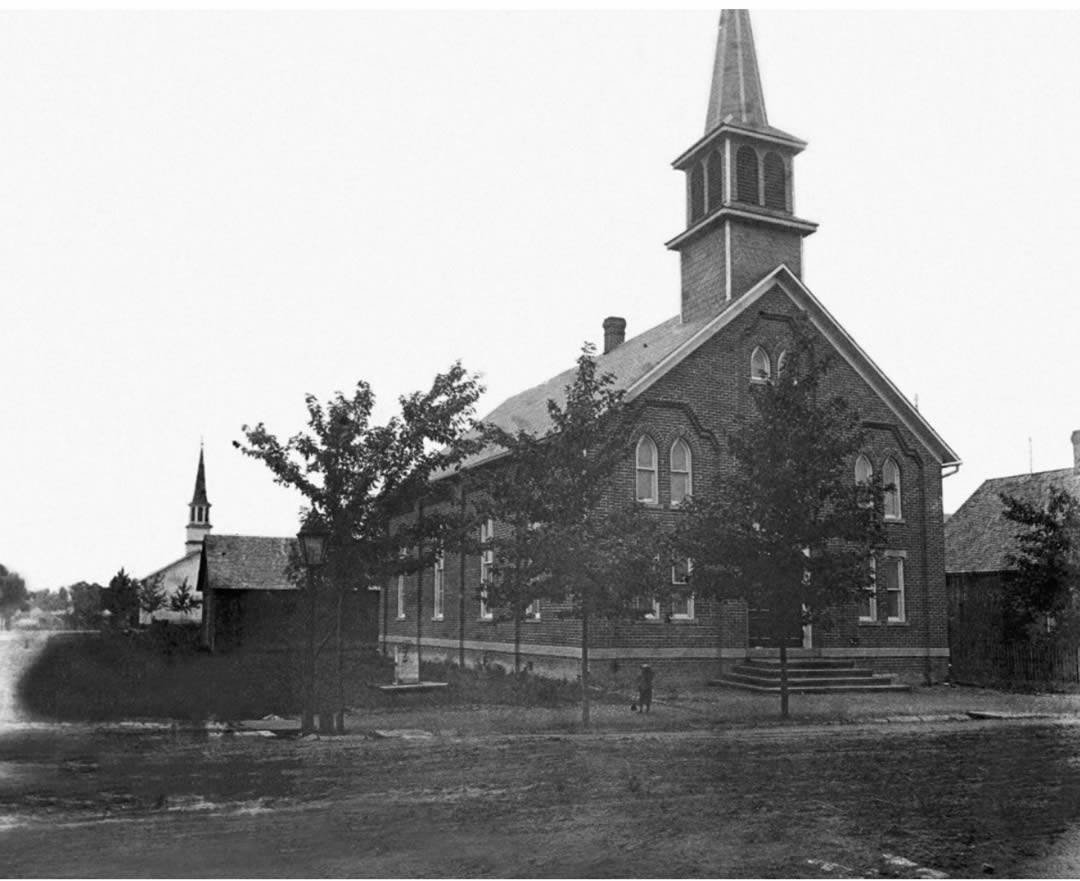

Almost as soon as the organizational proceedings for the new congregation had been completed, they set about to build their own church – a sizeable brick edifice 40 feet by 80 feet on the same location that is now occupied by the present Methodist Church. This building was completed and dedicated for service on the last Sunday in November, 1891.

The Emmanuels Church building was erected in 1891 and served that congregation until 1894. In 1899 it was purchased by the Methodist congregation and used by them until 1916, when it was razed and replaced by the current Methodist church building. The old Methodist frame building one block to the west is visible in the background.

Immediately upon completion of the church edifice, the congregation also built a frame parsonage on the south side of the village which was completed by March, 1892. This parsonage is the same building now owned and occupied by Noah Katterheinrich as his home.

In 1892, this new congregation was to make yet another acquisition – its own cemetery. On August 7, 1892 Mrs. Fredericka Niemeyer, the wife of William Niemeyer, had died at the age of 44 years. At that time the two cemeteries in the community were the exclusive property of the respective churches – the Reformed Church and the Methodist Church. No one had a title to any part of them, save that he was assured that he and his immediate family members would be laid to rest there, providing he was a member of either respective church.

Because of these burial regulations (exercised by both churches) the new congregation took immediate action to find a new burial ground for their departed member. Consequently, they purchased an acre of ground immediately south of the village limits, lying east across the road from the Hoge Lumber Company. Here Mrs. Niemeyer was laid to rest among the greatest floral display that ever graced a funeral – a clover field in full bloom. This cemetery and its many tombstones remain as mute evidence of this congregation, which was later to become re-absorbed into the Reformed Church.

The foregoing recital concerning the Emmanuels Church is but a part of the reactions that plagued the confused and strife-torn congregation so soon after Rev. Kuckherman’s retirement as their pastor. To him this was a matter of deep regret and great sorrow. The pulpit was vacant. More and more members attended services at the Emmanuels Church. As had happened once before in 1843, no new minister would accept the charge because of the rampant confusion existing in the congregation. Services were conducted by the church elders, visiting ministers and, every fourth Sunday, Rev. Kuckherman himself would conduct the services in an effort to keep the congregation alive.

In this struggle, Rev. Kuckherman could not afford to take sides. He had to remain neutral, but how could he when people by the droves visited him for his personal advice? Then suddenly he had an inspiration. All during his pastorate he had led his people by suggestion. Surely the Lord would let him do it again.

Quickly he planned to absent himself from the community where he would be free from these visitations. His grandson was to inform one and all that called for him that Rev. Kuckherman and his wife had gone to Cincinnati on an important business matter. Yes – he had gone to Cincinnati, and on the most important business of his varied and many-sided life – to heal the wound that had so deeply scarred his congregation. He was to be absent for more than three weeks.

When Rev. Kuckherman arrived in Cincinnati, his first call was upon a Dutch artist of that era, whose paintings he had learned to admire because of their realistic design and because of his ability to portray his subject matter in intimate detail. “I want you to work for me and to paint the masterpiece of your life – I will pay you well”, was Rev. Kuckherman’s request. The commission was promptly accepted.

And so these two men – the master planner and the master painter began to collaborate on producing their mutual “Masterpiece”. “Paint a picture of a majestic church, with simple and graceful lines and with a tall, massive, stately steeple that shall reach high into the heavens. In the tower must be a huge clock and a huge bell. Make it large – and do not mind the cost.” This was the request made by Rev. Kuckherman.

In their joint collaboration, the artist began to draw sketches of the proposed church. At first sketch after sketch was discarded because, for one reason or another, it did not represent all of the salient features Rev. Kuckherman desired. Finally, however, a sketch emerged that only needed further embellishments, which the artist provided. At this point Rev. Kuckherman gave his approval and the painter began to apply his artistry. Finally it was finished, and it was – indeed – a masterpiece. Rev. Kuckherman immediately had it appropriately framed, and he was now ready to go home and receive visitors.

When he arrived home, he placed the painting in the most conspicuous location in his otherwise book-studded living room. Because of its size (36 inches by 48 inches), it was grotesquely out of proportion to the rest of the décor in the room. But he had planned it that way, for he wanted it to draw the attention of every visitor.

The news of Rev. Kuckherman’s return spread throughout the community and the visitations resumed.

Naturally the topic of conversation concerned the strife and confusion still rampant in the congregation. To one and all he gave the same reply – simply, solemnly and directly spoken – “The situation that has so seriously afflicted the congregation is indeed grave and should be regretted by all. What difference does it make to the Lord whether the Congregation sings praises to him from a book that has notes, or one that has not, so long as the congregation sings? It is regrettable that this whole affair was triggered in anger, and that it might have been mellowed by earnest prayer. But it has happened, and now only through earnest repentance can the sins of anger and strife be stilled and forgiven.”

Thus he spoke to one and all, and it was noted that this very simple admonition was sufficient to stop further transfers from the Reformed Church to the Emmanuels Church. However, it was also noted that with one and all a deep curiosity was raised concerning the painting on the wall. When he was asked about it, he simply stated: “Oh, the painting – it is now of little concern. At one time it was my fondest dream that my congregation would build such a temple as thanksgiving to the Lord for the way he has prospered them.” However, with the congregation torn by strife, and because of his own ill health, this dream seemed impossible of realization.

Soon these people returned for another visit. This time nothing was mentioned about the strife in the congregation, for that matter had been settled. They came to take a closer look at his painting. Without exception every one admired the beautiful church edifice that the painting portrayed, but it would be so expensive. To this the Reverend replied, “If every member in the congregation would return to the Lord just ten percent of the prosperity he had permitted them, such a church could be built twice over”. Then there were some who reasoned that perhaps the church could be built by cutting corners and using less costly materials. To such he answered, “Would you give to the Lord anything but the best?”

And so, through the power of positive thought and his ingenious suggestion, an air of expectancy was beginning to permeate the congregation. His plan was beginning to work. Now he had another chore to perform – to find a qualified minister to serve the congregation. To fill this position would require an extraordinary person. For this he personally strove to induce Rev. Moritz Noll of Ragersville, Ohio, whom he personally knew and admired, to accept the pastorate – guaranteeing him his personal support. Later in 1892 Rev. Noll accepted the charge.

Rev. Kuckherman’s choice of Rev. Noll to accept the pastorate of the New Knoxville congregation deserves further comment. The engagement of Rev. Schneck had been a colossal error – not because of any incompetency on the part of Rev. Schneck, but because he had come from a city church, (Louisville, Kentucky) where he enjoyed great latitude in his ministerial administration. By bringing him to the staid, rock-ribbed New Knoxville congregation, it was only natural that his progressive views would be quickly resented. It is to be further noted that in July of 1893 Rev. Schneck left the Emmanuels Church and the New Knoxville community, being replaced by a Reverend Mathis as pastor.

Rev. Noll, on the other hand, was serving a small community church at Ragersville, Ohio (a town that has since gone out of existence), where his experience and his own innate ability as a preacher should more naturally qualify him for the New Knoxville community.

By the end of the year 1891, nearly every member had become excited about building a new church – one just like the painting hanging in Rev. Kuckherman’s sitting room. Soon a special committee came to call on him. Could they borrow the painting for a special congregational meeting they were holding, and did he have detailed plans for building this church? To this he answered, “You are welcome to borrow the painting. As for building plans I cannot help you. To build such a church would require the services of the very best architect you could engage”.

Soon afterward, Rev. Kuckherman was visited by the architect the congregation had engaged. To him Rev. Kuckherman confided his secret and asked that it not be revealed. Thus, quietly working in closest harmony with each other, a most carefully planned blueprint – as carefully and classically prepared as the painting itself – was made ready for presentation. At this point Rev. Kuckherman requested that henceforth the architect assume the full responsibility for all further developments, and that his name be excluded from any plans. He wanted all decisions to be made by the members, and therewith he ended his participation in the building project.

At a congregational meeting held on March 8, 1892 Rev. Moritz Noll was elected as minister, and he began his duties on November 20th of the same year. At the same time, Rev. Kuckherman now settled back to a life of peace and contentment, to enjoy the deep satisfaction of the fruition of his special endeavors.

The construction of the church proceeded at a rapid pace. For both the architect and the builder, this enterprise represented the builder’s dream – for any special problems that would arise, there would always be the same answer – “Use your own judgment, but make it the best”. Never before had there been such harmony in the congregation, nor such expectancy of achievement as was experienced with the building of this church.

Soon the building would be completed and dedicated. The date for its dedication was set for August 26,1894. A committee was sent to Rev. Kuckherman, asking him to preach the first sermon in the new church that they had built as a fulfillment of his dream. To them he answered, “You have built this church for the glory of God – not for me. I have had no part in its building. Now you have a new church and a new, good minister who deserves the right to dedicate it. No, this honor belongs to your minister, but if I should be asked to deliver the last sermon in the old church where I have served for many years, I would be happy to do so”.

So it was that on Sunday, August 19,1894, Rev. Kuckherman again spoke from the pulpit he had served in this same church from the time it was built to its very close. On that day there were no services in the Emmanuels Church for all of its members had formerly been members of Rev. Kuckherman’s congregation. The church was filled to overflowing and everyone was expectant of the message the master minister would have for them on that day.

The service on this particular Sunday was different from any the community had ever experienced and was long to be remembered. Seated among the regular members were former members who had left to organize Emmanuels Church, as well as members from the Methodist Church. The attendance was so great that several hundred people were forced to listen on the outside. This made no hardship for Rev. Kuckherman because of his strong, clarion clear voice, which carried well and far.

He began his sermon by a careful review of the events that had transpired over the years. He spoke of the trials and tribulations that had beset them at times, but he was careful to overshadow the remarks by commenting about the great achievements and prosperity they had achieved. Then came the heart of the message.

“Beloved”, he said, “during these years that you have asked me to be your minister I have tried to serve you to the best of my ability. But, because of human frailties, my efforts have many times been short of what they might have been. In our many private discussions, I feel also that my judgment was many times biased and colored to meet my own personal opinions. Today, these my many sins both of omission and commission to you, individually and as a congregation, lay heavily upon my heart, and I sincerely hope that you may have within you the forbearance to forgive my every overt act.”

As the congregation listened to his words of confession, the thought sprang into every listening mind – when, where, and in what regard had this great minister ever failed in his ministry, both to the congregation or to its members? How strange that this man should ask their forgiveness for faults he might have demonstrated through his labored career! What they did not realize was that again he was leading his listeners to make a careful review and self-analysis of their own personal lives.

For the remainder of his sermon he praised the congregation for the mighty labor of love they had demonstrated unto their God through the temple they had built in his honor. To those who had left the congregation to build another, he simply suggested that if any experienced a feeling of homesickness, they should not permit personal pride to keep them from returning. Come home – the feast of the fatted calf awaits you. This was his invitation for the reunification of the congregation, and so ended his services for them.

At the conclusion of this service, as the people filed from the church, there was not the usual bantering and visiting between members, as had been the custom. Each member left with an awesome burden of thoughts that required solemn contemplation in the privacy of his own home and with his family. It has been reported by older citizens who attended this service that every eye had moistened during the sermon, and that also everyone had a feeling of a certain cleansing effect upon their lives.

Except for his participation in the Dedication Services held on the following Sunday, August 26, 1894 when, along with Rev. Noll, he assembled the congregation in front of the old church and then together led them into the new church, his services of August 19, 1894 was actually his last official act of his congregational services.

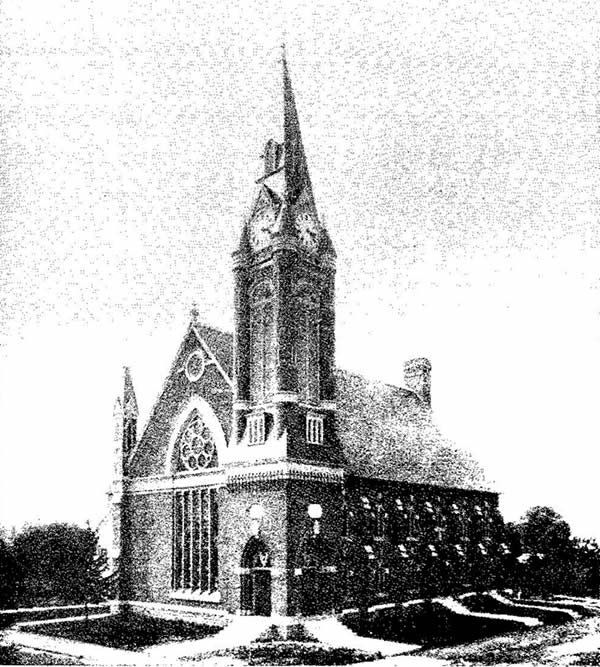

The new Reformed Church building, known as the Noll Church, as it was dedicated August 26, 1894

The effects of his sermon became quickly manifested. Because of it, a deeper sense of devotion became evident in the congregation, and it had also served to sound the death knell of the lately organized Emmanuels Church. Within eight months the Emmanuels Church was completely abandoned. All but two families (who joined the Methodist Church) had returned home to their erstwhile congregation.

For a number of years the abandoned Emmanuels Church building was used as a storehouse. Its final disposition is recorded in the congregational records of the present Methodist Church. This meeting, reported under date of May 29, 1899, was attended by H. W. Katterhenry, Wm. Meckstroth, Henry Knierim, William Kruse, H. Schrolucke, W. H. Fledderjohann and Rev. Max Dieterli. The minutes of this meeting state as follows:

“The purchase of the Emmanuels Church has this day been completed for a total price of $1,005.00. A payment of $100.00 has been made, with the balance to be paid ½ in 14 days and the remaining amount in 6 months.”

After the Methodist Church purchased the edifice, they repaired the structure and then used it for services until the year 1916, when under the pastorate of Rev. P. L. Philip, the building was razed to make room for their present modern and imposing house of worship. Thus has the Emmanuels Church been removed from the community scene, but the Noah Katterheinrich residence as its former parsonage, and the cemetery on the south side of the village bear mute evidence of the confusion and strife that once reigned in the community.

However, there was yet another consequence regarding the church edifice the congregation had built. When the official photograph of the completed appeared in the “Kirchenzeitung”, the official magazine of the Reformed Church, it drew the immediate attention of other denominations, causing it to be reproduced in many of the architectural magazines, which also praised it for its majestic and stately lines. Actually, it became a model of architectural design over which hundreds of churches were to be built all over America.

On the following page, we reproduce a copy of the original photograph taken at the time of completion and for the subsequent dedication of this “Miracle Church”.

The new Reformed Church building, known as the Noll Church, as it was dedicated August 26, 1894

It is unfortunate that the original painting so painstakingly planned by Reverend Kuckherman and painted by the artist has passed from the local scene, for its possession today would make it a treasured article of great worth.

The painting was sold by his grandson, Henry O. Kuck, as the administrator of Rev. Kuckherman’s estate in 1915, to an agent of the Central Publishing Company of Cleveland, Ohio, who had been invited to make an offer on the large collection of books which the Reverend had accumulated over the years. The painting was sold for $50.00. Should anyone reading this account have any information concerning the whereabouts of this painting, the author will personally offer $1,000 for its possession.

In such manner did the erstwhile minister come from his retirement to perform the greatest miracle of his varied life. Not only did he heal the sins of the anger and contention among the members of both congregations, but the healing consequences were to affect the entire community.

Carefully and through modest procedure he had led the congregation to the very highest pinnacle of achievement – one that had not been paralleled before or since by any other religious congregation.

Thus by year’s end in 1894, we find the dissolution of the Emmanuels Church and the re-unification of the Reformed Church. The Methodist Church profited by nine members that transferred from the Emmanuels Church – those members representing branches of the Lageman and Rodeheffer families.

It is at this point that the author chooses to end his account concerning the early historical events affecting both churches. Subsequent events are fully recorded in the minutes of the respective churches and may be easily followed from this point.

We also note, at this stage, the second retirement of Rev. F. H. W. Kuckherman from the ministerial scene to become again plain Henry Kuck – the scientific farmer – and it is in this position that he would devote another twenty-one years of concentrated thought, study, and practice.

In concluding this treatise, it may be of interest that the work of Reverend Kuckherman and the church he founded has been recognized as one of the truly great pioneering efforts in the State of Ohio.

In the fifth edition of “Ohio Builds a Nation” by Samuel Harden Stille, which is an historical account of early pioneering life in Ohio, a full page (#330) – complete with illustrations – is accorded to Reverend Kuckherman and the church which he founded.

By special permission of its author, Page 330 of “Ohio Builds a Nation” is herewith reproduced.

NOTE: The farm in Shelby County which was purchased by Ernst Kuck when he sold his interest in the tile Mill, and which was later owned and operated by Lewis Kipp, is located at 8363 Botkins Road.

NOTE: The house that served as the Emmanuels Church Parsonage, and which was occupied by Noah Katterheinrich at the time of E. R. Kuck’s writing is located at 502 South Main Street.